KEY FINDINGS

Presented here are findings from Phase I of the Promoting At-Promise Student Success (PASS) Project. This six-year mixed methods study explored a comprehensive college transition program (CCTP) that serves low-income, primarily first-generation students, as well as racially minoritized students (whom we collectively refer to as “at-promise” students).

The goal of the study was to understand whether, how, and why the CCTP develops a set of traditional academic short- and long-term outcomes such as retention and GPA, and a set of key psychosocial outcomes (described below) that capture important facets of the college student experience and are associated with persistence and graduation. This work makes several contributions to the student success movement and in promoting equitable outcomes for at-promise students.

To learn about emerging findings from PASS Phase II, please visit our Project Updates page.

What Kind of Intervention Did We Study?

These findings add to an emerging research base around CCTPs. Thanks to research conducted over the past decade, policymakers, practitioners, and foundations are understanding that single interventions (e.g. one-time programming), located mostly in the first year, are often not effective for increasing postsecondary outcomes for at-promise populations. As a result, institutions are investing in comprehensive programs that vary in length from a semester to four years and provide an array of support for at-promise student populations. The researchers on this project developed a typology of these programs to aid future work within this literature base, please see: Hallett, Kezar, Perez, & Kitchen, 2019.

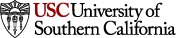

Study findings results from research conducted with the Thompson Scholars Learning Communities (TSLC), a CCTP that includes multiple program elements:

Program Elements

- Program Staff: Full-time staff who work with students to provide academic, social, career, and personal support.

- Shared Academic Courses: General education courses where enrollment is limited to TSLC students. Students enroll in two shared academic courses each semester during their first year. In their second year, students enroll in one or two shared courses based on campus requirements.

- First-Year Seminar: A course taught by TSLC staff to build academic skills and create community.

- Proactive Advising: A mid-semester intervention to provide academic assessment and guidance. Students are required to get feedback on their academic progress in each of their courses and then meet with TSLC staff and faculty to discuss.

- Peer Mentors: Returning TSLC students serve as peer mentors and academic leaders.

- Academic, Social, and Career Events: Events planned by CCTP staff that build skills and foster community. Some events are required and others are optional.

- Shared Housing/Space: Dedicated residence halls or floors, study spaces, and/or offices that facilitate socializing, studying, and community events.

- Financial Support: Students receive the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation Scholarship to assist in covering college expenses, primarily the cost of tuition, for up to five years.

Through these CCTP elements, students have structured and unstructured opportunities for meaningful academic and social interactions with key CCTP affiliates including staff, instructors/faculty, and peers. These interactions are important aspects of the program that cut across multiple program elements.

What Did We Study?

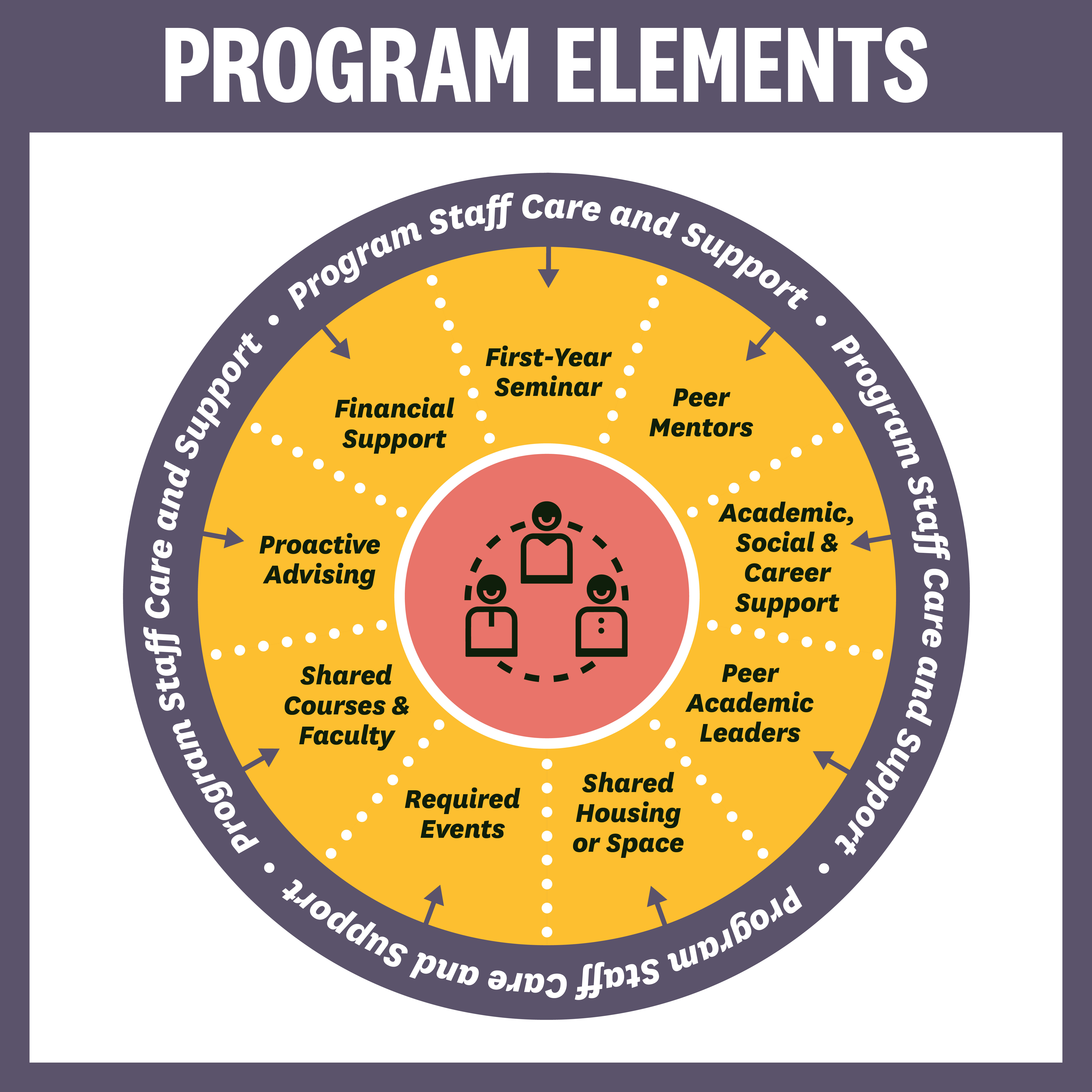

The PASS project explored and documented whether, how, and why TSLC programs produced positive student academic and psychosocial outcomes. Measures of student success not only included traditional academic short- and long-term outcomes such as retention and GPA, but also psychosocial outcomes such as validation, mattering, and sense of belonging as well as academic, social, and career self-efficacy.

The researchers conceptualized students’ college experience in terms of Astin’s student engagement model (1993 2 ).

We aimed to better understand students’ college experiences, with a particular focus on CCTP experiences. The findings focused on key psychosocial outcomes that have been linked to student success:

- Mattering: The extent to which a student perceives themselves to be valued as an individual and that others care about their personal wellbeing and success. [We examined students’ mattering to both TSLC and the campus as a whole (Rosenberg & McCullough, 1981 3 )].

- Sense of Belonging: The extent to which a student feels connected to a group, accepted by their peers, and that they are an integral part of the campus community. [We examined students’ belonging to both TSLC and the campus as a whole (Strayhorn, 2019 4 )].

- Academic Self-Efficacy: The extent to which a student feels they can succeed academically (Zimmerman et al., 1992 5 ).

- Social Self-Efficacy: The extent to which a student feels they can successfully navigate social interactions (Anderson & Betz, 2001 6 ).

- Career & Major Self-Efficacy: The extent to which students are able to successfully decide on a major and career path (Betz, 2006 7 ).

- Validation: A proactive process of affirmation and recognition of students’ abilities as scholars and their diverse assets by institutional agents including instructors and staff. Validation encompasses two forms: academic and interpersonal (Rendón, 1994; Rendón & Muñoz, 2011 8 ). In this study validation is not a direct outcome, but is a process that facilitates positive psychosocial outcomes.

The research team additionally examined cumulative GPA and persistence and degree attainment as measures of students’ academic success.

What Did We Learn?

Over the course of six years, the PASS Project research team generated findings to expand knowledge about how postsecondary institutions, CTTPs and practitioners can best support at- promise students’ success. Below we share selected findings in response to a series of questions about the CCTP.

Are Psychosocial Outcomes Key to Academic Achievement and Persistence?

Key Psychosocial Outcomes are Linked to Academic Outcomes

For all students, regardless of CCTP participation, higher reported psychosocial outcomes were associated with an increase in GPA and persistence in enrollment

Does the CCTP Work?

The CCTP Developed Key Psychosocial Outcomes

The experimental evaluation concluded that participating in the CCTP had a positive impact on mattering, sense of belonging and career and major self-efficacy. This experimental evaluation found no significant impact of CCTP participation on academic or social self-efficacy.

The CCTP Increases Career and Major Self-Efficacy, Which is Associated with Persistence

The team’s mixed-methods research explored an area where very little research exists for at- promise populations – career and major self-efficacy. Data illustrated how taking a developmentally appropriate, ecological approach to designing major and career programming aimed at developing confidence in one’s major and career path allowed at-promise students to flourish. Given the emerging data on the relationship between having postgraduate plans and persistence for at-promise students, these findings have clear implications for college campuses working to support these populations.

The CCTP and Similar Programs can Increase the Participation of Underrepresented Groups in STEM Majors

Mixed-methods data show how CCTPs empowered at-promise students–particularly racially minoritized students–to choose and be successful in majors in which they have been traditionally underrepresented, such as STEM. Given the challenge of moving at-promise students into STEM fields, these insights can advance efforts in this area.

For Whom is the CCTP Impactful?

The CCTP Successfully Promotes Equal Engagement Across Groups Defined by Demographics and Academic Preparation

Students engaged at similar levels with elements of the CCTP (e.g., by participating in discussions in shared academic courses or developing relationships with mentors) across groups defined by race, ethnicity, sex, first-generation status, income, and academic preparation. These are significant findings because few programs are able to serve students from very different backgrounds successfully. The practices employed by the CCTP worked equally well across various student groups. Typically, campuses have created a plethora of support programs for dozens of individual student subgroups, a resource-intensive way to support students. This research suggests approaches that work equally well across all at-promise groups may be deployed in more efficient ways.

The CCTP Develops Psychosocial Outcomes for Most Students with Multiple Marginalized Backgrounds

Students from low-income backgrounds, racially minoritized, students with lower levels of academic preparation, and first-generation students experienced the largest effects of the CCTP on mattering to campus. This is an important finding as students from these demographic backgrounds are increasing their participation in higher education but face challenges in completing their degrees.

Why Does the CCTP Work?

Important Relationships Exist between Key Psychosocial Outcomes and Supporting At-Promise Student Groups

The mixed-methods evaluation of the CCTP examined multiple psychosocial outcomes. While the data do not allow a full test of the causal relationships between these constructs, the researchers brought together different pieces of evidence to suggest hypotheses for how these constructs are related and call for future research rigorously evaluating these relationships. The experimental evaluation of the CCTP shows that participating in the CCTP increased students’ sense of belonging during their first two years and reported feelings of mattering during their first three years on campus. Descriptive quantitative analyses of students in the CCTP indicated that higher levels of belonging in students’ first year were associated with higher levels of mattering in students’ second year. Qualitatively, feelings of belonging and mattering may have contributed to students’ sense of academic self-efficacy. Using qualitative and descriptive quantitative analyses, we also show that validation is a key lever underlying both belonging and mattering. Based on these results, the project team hypothesizes that validation may help students to establish a foundation of belonging, which then grows alongside increases in mattering. Having these strong relationships and connections to campus then help students feel confident in academic settings, which may promote academic success.

Validating Approaches Prove Effective

The mixed-methods data help to provide evidence that the implementation methods used by CCTPs were more important than the specific elements (e.g. mentoring, learning community) included in the CCTP. In other words, how you implement policies and practices matters. A validating approach among faculty, staff, other institutional agents, and peers affirming students’ capabilities for success was more important than specific programmatic elements. Validation was important to at-promise students, low performing students, and all subgroups examined.

A Culture and Ecology of Validation Supports Students Across All Marginalized Identities

The CCTP was successful because it created a culture of ecological validation. Students feeling validated as learners acted as the most important lever for at-promise students. An ecology of validation involves proactive, holistic, asset-based, and tailored support that is offered at multiple touchpoints over time; a culture embeds validation into the CCTP’s values, policies, practices, rituals, and traditions. These findings are particularly important as they run counter to much of the student success literature that focuses on interventions, particularly technology. As validation is developed through human interactions, student success efforts need to focus much more centrally on the training and support of faculty, staff, and paraprofessionals on campus.

Focus on Students’ Sense of Mattering Facilitates Success

Much of the research in higher education has focused on a sense of belonging to the detriment of focusing on mattering. This study’s findings suggest that as campuses work to create better climates, focusing on helping students feel like they matter to someone on campus is critical. Students may be more successful not only when they feel like they are part of campus, but also when they feel their goals, successes, disappointments, and experiences are valued.

Tailoring Support and Creating Multiple Pathways for Students is a Key Lever for At-Promise Student Success

Various analyses revealed that different CCTP components lead to the same psychosocial outcomes for different groups of students. For example, staff care and support were associated with mattering for female students, whereas faculty interactions were associated with mattering for male students. Tailoring is a process in which lessons that emerge from individual students are scaled to create broader change and to support students from different programs (Kezar et al., forthcoming; under review 9 )

The mixed-methods research identified tailoring practices and processes used by CCTP staff, including one on one meetings, focus groups, surveys, communication with other CCTP offices, communication across faculty and staff, and the use of peer mentors. These practices and processes can be scaled to thousands of students. These findings suggest that program consolidation should be considered with care. In hard economic times, campuses may be looking for ways to narrow support programs. This study suggests that having a variety of different program interventions was necessary to obtain equal outcomes because different elements were associated with the successes of different student groups.

Flexibility in Implementation Allows for Similar Student Outcomes Across All Campuses

The CCTP was modified at each campus slightly to meet the needs of the student population and the mission of the institution. However, even with these slight modifications, the research team found that the CCTP produced similar outcomes for students at each campus, challenging the notion that strict fidelity is needed to garner the desired outcomes. This finding is important as policy research often emphasizes strict implementation fidelity but this study demonstrates that such fidelity may have compromised rather than supported outcomes and campus leaders should consider ways that programs may need to be modified to best fit their student population and context.

What are Key Effective Practices of the CCTP?

Identification of Key Practices of the Program

While the validating delivery of the CCTP is much more important than specific programmatic elements, this research identified several program practices that reflect exemplary approaches for supporting at-promise student populations in the following elements – a proactive advising process; shared academic courses, including an autobiography course; the care and support of program staff in one-to-one mentoring; and academic and social peer interactions. Even though the data emphasize the importance of how program elements are implemented over what elements are offered, the study and papers describe practices that campuses should consider as they design their CCTPs.

Interventions and Approaches can be Tested and Piloted Locally and then Expanded to Serve the Larger Campus

This study identified how a CCTP can serve as a “hub of innovation” for the larger campus, scaling changes that work for at-promise populations. The researchers identify the key mechanisms that helped the hub to effectively serve this role – creating an advisory board with stakeholders from the larger campus, developing partnerships with offices across campus, establishing coordinated networks with department chairs and academic departments, and facilitating staff and faculty joint meetings. These findings are important for campuses across the country that are trying to identify approaches for scaling effective practices and changing the overall campus environment or culture.

References

- The survey captured additional constructs, such as resiliency, college knowledge, and financial stress, that remain to be explored.

- Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college: Four critical years revisited. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Rosenberg, M., & McCullough, B. C. (1981). Mattering: Inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Research in community & mental health.

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2019). Sense of belonging and student success at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A key to strategic enrollment management and institutional transformation. Examining Student Retention and Engagement Strategies at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, 32-52.

- Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676. doi:10.3102/00028312029003663.

- Anderson, S. L., & Betz, N. E. (2001). Sources of social self-efficacy expectations: Their measurement and relation to career development. Journal of vocational behavior, 58 (1), 98-117.

- Betz, N. E., & Hackett, G. (2006). Career self-efficacy theory: Back to the future. Journal of career assessment, 14(1), 3-11.

- Rendon, L. I. (1994). Validating culturally diverse students: Toward a new model of learning and student development. Innovative higher education, 19(1), 33-51.; Rendón, L. L., and Muñoz, S.(2011). Revisiting validation theory: Theoretical foundations, applications, and Extensions. Enrollment Management Journal, 5(2), 12-31.

- Kezar, A., Kitchen, J., Hallett, R.E., Estes, H., & Perez, R. (accepted for publication). Tailoring programs to best support low-income, first-generation, and racially minoritized college student success. Journal of College Student Retention.; Kezar, A., Perez, R., Kitchen, J.A., & Hallett, R. (Under Review). Learning how to tailor a program to support low-income, first generation, and racially minoritized student success. Department of Education, University of Southern California.