METHODOLOGY

The PASS project consisted of two multi-institutional, mixed methods, longitudinal studies involving intentional collaboration among researchers, diverse university stakeholders and funders. Phase I of the PASS study followed two cohorts of first-time, low-income college students who entered college in 2015 and 2016 at one of three University of Nebraska campuses and who participated in the TSLC comprehensive college transition program. The study team used an integrated, iterative mixed-methods design to investigate research questions related to traditional academic short- and long-term outcomes such as retention and GPA as well as psychosocial outcomes such as academic self-efficacy, career/major self-efficacy, validation, mattering and sense of belonging. In the second phase of the study, researchers continued to use an integrated, iterative mixed-methods design and have expanded the study to include students who did not participate in the TSLC program. Phase II of the study continued to explore relationships between academic and psychosocial outcomes and expanded inquiry to include social class identity, well-being and time use/management. Phase II also included multiple case studies of professional learning communities designed to promote at-promise student success at three University of Nebraska campuses.

Both phases of our multi-institutional, mixed-methods, longitudinal Research Practice Partnership involved:

- Intentional collaboration among researchers, university practitioners & funder

- Regular and longitudinal structured and unstructured communication about emerging findings, implications for practice and future directions for research

- Joint publications and presentations

PASS I 2015-2019

Mixed-methods project examining whether, how, and why the key elements of the Thompson Scholars Learning Communities facilitated the development of psychosocial and academic outcomes among at-promise students.

PASS II 2020-2025

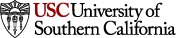

Mixed-methods project designed to (1) better understand how all NU at-promise students’ psychosocial and academic outcomes change over time and relate to their experiences on campus (TSLC + non-TSLC); ad, (2) examine programmatic and institutional change processes in support of at-promise student success.

PASS - Phase II

The second phase of the PASS study expands on phase I findings and involves an actionable mixed methods, longitudinal research approach.

Research Questions – Phase II

The study was guided by four sets of research questions. The first two sets focused on student experiences, the third set on the Thompson Scholar Learning Community (TSLC) programs and related practitioners, and the last one on the University of Nebraska and institutional leaders. RQ1 and RQ2 center students’ experiences and required a mixed-methods approach, with the qualitative team providing sense-making of the quantitative findings. RQ3 and RQ4 primarily involve qualitative case study data involving faculty, practitioner and administrator perspectives.

Research Question #1 (RQ1)

How do the psychosocial and academic success outcomes of at-promise students change over time and relate to their program engagement and other student experiences?

Research Questions #2 (RQ2)

How do students experience career and major self-efficacy after the end of the formal TSLC program? How do program stakeholders and students experience the programmatic career and support changes resulting from the PASS1 study? What are the lessons learned that could be scaled to an institutional level? How do TSLC students’ career and major self-efficacy compare to their peers?

Research Questions #3 (RQ3)

How do TSLC programs make sense of the research findings and recommendations related to the PASS1 study? How do TSLC stakeholders within the programs make changes as a result of the research findings? How do Communities of Practice (CoPs) help facilitate the implementation process? What practitioner-based resources help to facilitate the implementation process?

Research Questions #4 (RQ4)

How do campus agents promote at-promise student success in meaningful and sustainable ways? How do change agents make sense of research findings related to an ecology of validation? What institutional and relational support do they need in order to scale and implement an ecology of validation? What levers are used? What are the barriers and challenges?

Research Foci

Key Constructs

- Academic Self-Efficacy: The perceived capabilities of individuals to complete certain academic tasks given particular contexts (Pajares, 1996). According to Bandura (1977), this concept has four resources: vicarious experiences/social modeling, performance accomplishment/mastery experience, verbal persuasion/verbal feedback, and emotional and physiological state.

- Ecological validation: A particular focus on students’ experiences of being connected to resources and support offices they need by an instructor, staff member, peer, or advisor so as to enable their academic or personal success and to help them achieve their academic and/or personal goals.

- Financial stress: The adverse emotional and psychological effects of concerns about affording college and meeting other financial obligations. Although scholarship funding provides a generous resource, financial stress may still be a factor as students navigate basic needs (e.g., food, housing, technology) as well as security for themselves and their families and can be a factor for students who do not receive a scholarship.

- Financial wellbeing: Personal circumstances where students can meet their current and ongoing financial responsibilities, make everyday purchases without feeling stress, effectively cope with unforeseen financial events, and pursue their long-term financial goals.

- Major and career decision-making: The belief in one’s ability to successfully complete the necessary tasks to make decisions about a career (Taylor & Betz, 1983) and, relatedly, about academic plans of study.

- Mattering: A motive or “the feeling that others depend on us, are interested in us, are concerned with our fate, or experience us as an ego-extension” (Rosenberg & McCullough, 1981, p. 165).

- Metacognition: The process of acknowledging and monitoring one’s own cognitive activities (Flavell, 1979). This “thinking about thinking” is crucial for understanding how students are proactive in their own learning. Metacognition considers understanding of one’s own cognition, as well as reflection on and application of that knowledge.

- Psychological well-being: The presence of positive emotions, interpersonal connections, and positive functioning, as well as the absence of ill-being. This approach is a hybrid of Ryff’s (1989) as well as Ryan and Deci’s (2001) broad distinctions between subjective/hedonic well-being and psychological/eudaimonic well-being. Hedonic well-being represents what many people think about in terms of well-being (e.g., happiness, lack of anxiety and stress, life satisfaction), while eudaimonic well-being is more consistent with a general conception of thriving or flourishing that extends beyond momentary emotional states.

- Sense of Belonging: The “perceived social support on campus, a feeling or sensation of connectedness, the experience of mattering or feeling cared about, accepted, respected, valued by, and important to the group (e.g., campus community) or others on campus (e.g., faculty, peers)” (Strayhorn, 2012, p. 3).

- Time management: The strategies, choices, and behaviors that students employ to manage their time, including how they manage and prioritize multiple time commitments.

- Time use: How students spend their time day-to-day, what they spend their time on (e.g., academics, socializing, working), and how students engage with the world around them.

Mixed Methods by Research Question

Research Question #1 (RQ1)

The primary analytic sample for RQ1 includes all incoming TSLC students in the Fall 2021 and Fall 2022 cohorts, as well as all incoming non-TSLC in-state NU students with Expected Family Contributions (EFC) of no more than $10,000 from the same two cohorts. We administered a pretest to this group at the beginning of their first year and post-tests at the end of their first and second years.

A subsample of students were selected to interval surveys that involved repeated short assessments over time to explore constructs that are critical to student success and that may fluctuate notably over time: academic self-efficacy, mattering, validation, and well-being. These students also provided open-ended and closed-ended responses about events in their lives that affected their college experience.

Another group of first-year, second-year, and third-year students was recruited to participate in time-use surveys that provided real-time information about their time use during the Fall 2022 semester. These students were asked to respond to several messages sent at random times throughout the day over the course of one week that asked what they were doing, who they were with, and how they were feeling at that moment. The interval and time use surveys oversampled students from key populations of interest, including Black and Latinx students, first-generation students, male students, students with lower precollege academic preparation, and students who had not declared a major.

We also conducted longitudinal interviews with first- and second-year students at each campus. Interviews were intended to deepen understandings of emerging quantitative findings as well as to gain a nuanced sense of the study constructs mentioned above.

Research Questions #2 (RQ2)

Interval surveys and interviews will be used in Years 3 and 4 of the study to explore the experiences and outcomes of students who are beyond the second year of college, with a focus on major/career outcomes. The interval surveys will assess students’ career/major self-efficacy, career preparation, and career plans. Interviews will provide nuanced data about major and career efficacy and plans.

Research Questions #3 (RQ3)

In order to further learn about the TSLC program, the research team will continue to learn from TSLC directors, practitioners, and faculty through interviews, observations, and document analysis. The research team also regularly collaborates with TSLC stakeholders in the sense-making process.

Research Questions #4 (RQ4)

Developing an understanding of how the Professional Learning Communities cultivate a culture of ecological validation on their campuses includes observations of meetings, surveys to solicit PLC member feedback on processes and outcomes, interviews with PLC participants, document analysis and sense-making in collaboration with PLC participants.

Research Questions & Overarching Design – Phase I

The Specific Research Questions that Informed this First Study

Understanding Students' Experiences and Outcomes

- How do faculty and classroom experiences shape students’ program engagement and outcomes?

- How do different students engage with the TSLC program, and how does this engagement appear to shape their experiences and outcomes?

- How do key program components shared across the three campuses facilitate engagement, the development of academic self-efficacy, mattering, sense of belonging, and the other study outcomes?

- How do differences in the programs across the three campuses affect engagement, shape the development of academic self-efficacy, mattering/sense of belonging, and the other outcomes?

- How do regional differences (i.e. rural, urban, suburban) shape students’ program experiences and outcomes?

- How does the TSLC experience affect particular subgroups, including racially minoritized students, low-income students, and students with different levels of academic preparation?

- How do TSLC scholars experience their transition out of the program, and how might this experience affect their continued educational success (retention and graduation), academic self-efficacy, and mattering/sense of belonging?

Understanding the Impact of TSLC Participation

- Are there differences in the psychosocial and traditional academic outcomes between the students who experienced the TSLC compared to those who did not?

- Are there differences in the psychosocial and traditional academic outcomes between the students who experienced the TSLC compared to those who did not, depending on campus type?

- Are there differences in the psychosocial outcomes between students who participated in the Comprehensive College Transition Program (CCTP) and received financial support and those who only received financial support, the College Opportunity Scholarship (COS)?

- Are there differences in the psychosocial and traditional academic outcomes between the students who experienced the TSLC compared to those who did not–by selected student characteristics (e.g. racially minoritized students)?

Research Foci

This study was guided by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model (1979; 1994 1) and Rendòn’s validation theory (Rendòn, 1994 2; Rendòn & Muñoz, 2011 3). Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model contends that the human condition is best understood within context. At the core of ecological systems theory (EST) is the idea that humans are active individuals within evolving, interconnected, nested environments; the interaction between environments and humans are bidirectional, mutually exerting influence on one another. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model allows for greater customization of our understanding of the needs and experiences of different individuals in varying contexts. In a college system, students’ needs may be identified by program staff, who then facilitate the attainment of resources from different student services across the college.

Validation theory contends that student validation occurs when institutional agents, such as faculty and staff (and in some cases peers), take initiative to identify students as capable learners, as part of the learning community and as creators of knowledge, while also fostering students’ social adjustment (Rendòn, 1994 2; Rendòn & Muñoz, 2011 3). Validation can take two forms: academic and interpersonal. Academic validation includes actions by institutional agents that foster academic development. Interpersonal validation consists of actions that foster the students’ social adjustment to the institution.

The research was also guided by various frameworks that depict how students’ background characteristics, and prior experiences, as well as their college environments, shape their college engagement and experiences, impacting their outcomes (Hurtado et al., 2007 4 ; Museus, 2014 5 ). The outcomes studied focused on aspects of psychosocial wellbeing that have been linked to student success:

- Mattering: the extent to which a student perceives themself to be valued as an individual and that others care about their personal wellbeing and success. We examined students’ mattering to both TSLC and the campus as a whole (Rosenberg & McCullough, 1981 6).

- Sense of Belonging: the extent to which a student feels connected to a group, accepted by their peers, and that they are an integral part of the campus community. We examined students’ sense of belonging to both TSLC and the campus as a whole (Strayhorn, 2019 7).

- Academic Self-Efficacy: the extent to which a student feels they can succeed academically (Zimmerman et al., 1992 8).

- Social Self-Efficacy: the extent to which a student feels they can successfully navigate social interactions (Anderson & Betz, 2001 9).

- Career & Major Self-Efficacy: the extent to which students are able to successfully decide on a major and career path (Betz, 2006 10).

- Validation: a proactive process of affirmation and recognition of students’ abilities as scholars and their diverse assets by institutional agents including instructors and staff. Validation encompasses two forms: academic and interpersonal. In this study validation is not a direct outcome, but is a process that facilitates positive psychosocial outcomes (Rendòn, 1994 2; Rendòn & Muñoz, 2011 3).

We also collected more direct measures of students’ academic achievement and success:

- Course & Cumulative GPA

- Persistence & Degree Attainment

In addition, the researchers studied resiliency, college knowledge, financial stress, and perceived academic control, but at this time have not yet fully explored these as extensively as the outcomes above.

Research Methods

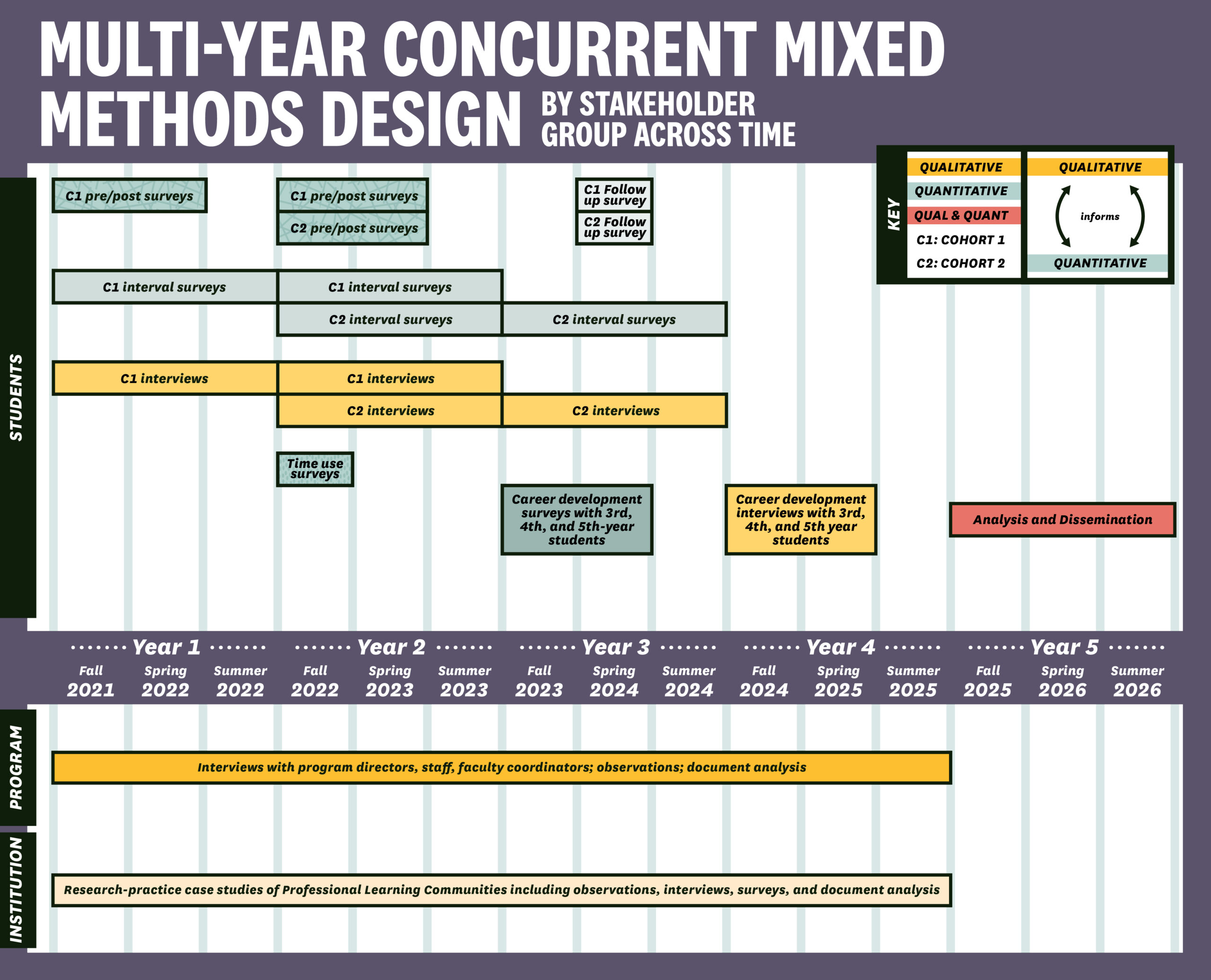

The study entailed multi-year concurrent mixed methods design. The study team used quantitative methods to examine differences in the outcomes of students who participated in TSLC compared to those who did not and to examine the experiences, perceptions, and behaviors of students in and outside of the program. The researchers also used qualitative methods to explore the experiences, perceptions, and perspectives of TSLC students, as well as TSLC staff members, instructors, and other key stakeholders.

Quantitative

The main source of quantitative data was a longitudinal survey, which the researchers used to draw connections among student characteristics, traits, attitudes, and behaviors; TSLC and college experiences; and various psychosocial outcomes.

Longitudinal Survey

Survey data were collected across two separate cohorts, at seven timepoints, from the three groups of students included in the study: TSLC students, College Opportunity Scholarship students, and control students. The study team conducted the initial survey during the fall of students’ first year of college to capture data on pre-college experiences and college expectancies. In each spring of students’ first through fourth years of college, researchers conducted a follow-up survey to capture data related to students’ engagement and behaviors in college, key outcomes, and, for TSLC students, engagement in the program. Informed by the study’s theoretical framework, the surveys included measures related to the following:

- High school behaviors and interactions [interactions with teachers, interactions with peers, volunteering, working, etc. (baseline only)]

- Psychosocial outcomes [sense of belonging, sense of mattering, academic self-efficacy, etc. (all seven time points)]

- College experiences and behaviors [high-impact practices, course engagement, interactions with faculty, time usage, student support services usage, etc. (follow-up surveys)]

- Academic choices and goals [college major, highest intended degree, post-graduation plans, etc. (follow-up surveys)]

- TSLC experiences [TSLC course engagement, interactions with TSLC faculty, interactions with TSLC staff, transition out of the program, etc. (follow-up surveys for TSLC students only)]

For more information about the iterative, mixed methods design of the survey, see Cole et al. (2019) 11

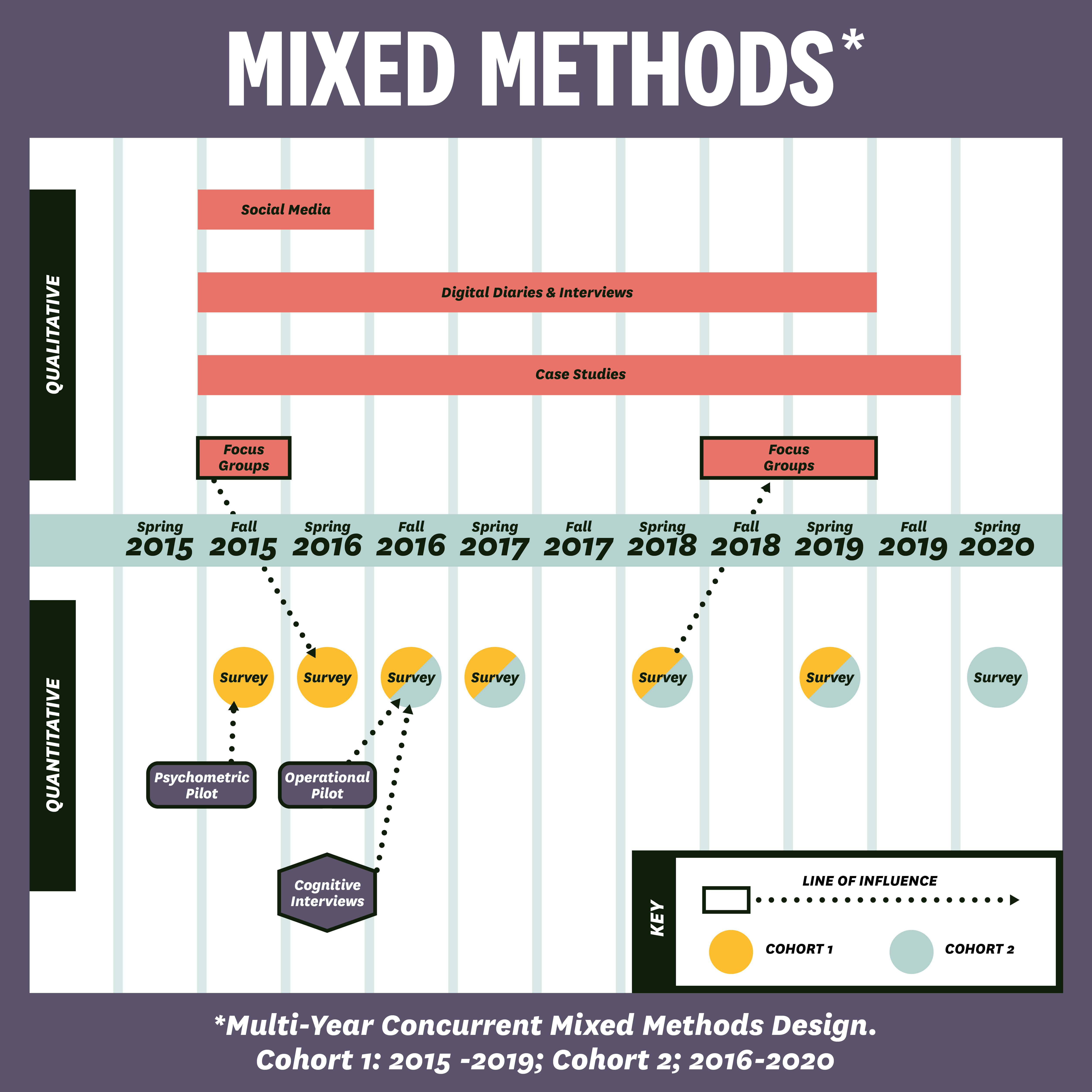

Randomized Control Trial

To carry out the study we collected longitudinal survey data involving a sample of STBF applicants who participated in a randomized control trial (RCT) evaluation of the program (see MIT study). The survey administered by the researchers included three distinct student groups using a partially randomized control design: TSLC students who received both a scholarship and access to the TSLC program, College Opportunity Scholarship (COS) students who received a scholarship alone, and control students who received neither a scholarship nor access to TSLC.

Survey Sample and Response Rates

The study’s main source of quantitative data was a longitudinal survey (described above). Researchers administered the initial survey during the fall semester of the first year for each of the two cohorts and proceeded with an annual spring survey. Below are the response rates for each treatment group by each survey administration.

Additional Quantitative Data Sources and Psychometric Information

Other Quantitative Data Sources

The research team also collected data from other sources to allow for comparisons across groups:

- Social identities and background [race/ethnicity, sex/gender, parental education, etc. (application to STBF)]

- Financial data and background [expected family contribution, last high school attended, etc. (FAFSA form)]

- Transcript data [course enrollment, credits attempted and earned, course grades, cumulative GPA, etc. (NU System)]

- Enrollment data [semesterly enrollment data at any postsecondary institution (National Student Clearinghouse)]

Weighting and Imputation

Even though obtained response rates were quite high for longitudinal college impact research, some students in the study population did not respond to all surveys. Therefore, survey weights were created for the purpose of correcting for potential nonresponse bias. Further, in all data collections, some individuals did not respond to all of the items on the survey. While the survey had very low rates of item nonresponse (all items had at least 95% item response rates among those who took the survey). Data missing due to item nonresponse on the TSLC survey data were imputed using a hot deck imputation procedure.

Measuring Students' Latent Traits

People’s latent traits (e.g., self-efficacy, sense of belonging) are not directly measurable. Rasch models are one strategy that allowed the research team to use responses to survey items to generate estimates of an individual’s score relative to a construct. The main goal of the psychometric analyses was to create scale scores using the Rasch rating scale model that would allow for direct comparison between cohorts and timepoints (for example, to examine change over time) for the survey measures.

The Rasch rating scale models used in the PASS project (Andrich, 1978 12 ; Wright & Masters, 1982 13 ) enabled the researchers to transform ordinal responses (e.g., “Strongly disagree”) into interval scale measures, and to evaluate the psychometric functioning of the scales (i.e., Is this scale producing reliable and valid data for interpretation by analysts and stakeholders?). Rasch rating scale models are not sample dependent (Granger, 2008 14 ), making them ideal for examination of measurement properties of a scale used beyond the scope of the data set being examined. Furthermore, the Rasch rating scale model can be used to create construct-level scores for individuals that summarize the results of their responses to multiple items that take into account the varying difficulty of endorsing the items that make up the scale.

Specific information about each of the Rasch constructs included in the PASS project, including detailed reporting about their reliability and validity, can be found in the following report.

Qualitative

Case Studies

Case studies of the three campuses were conducted via observations of various program components; interviews with faculty, staff, and campus stakeholders to understand goals and processes; and documentation of social and print media. The case studies served two main purposes: to better understand the program elements in the three different campuses and to document the ways the program operated to shape student experiences. The researchers were able to better capture how and why the program works by spending extensive time observing the programs’ elements such as, shared courses, first-year seminar, required academic and social events; participating in events, understanding the history of programs, and viewing the ways that groups and individuals interact.

Digital Diaries and Interviews

Student digital diaries (self-created videos) allowed researchers to obtain data continuously over time (as opposed to snapshots in interviews) and from the students’ perspective (as opposed to interviews where researchers lead the questioning). The purpose of the digital diaries was to develop a deep and holistic understanding of the student experience in the program. The researchers conducted detailed follow-up interviews every four to six weeks to explore questions generated by the videos. In these interviews, questions were asked that related to the students’ own backgrounds and experiences (e.g. commuter student status), their perceptions of the program (e.g. relationship with mentors), and other themes that emerged through a review of the digital diaries.

Focus Group Discussions

Student focus group discussions served three main purposes: to help explain the survey and qualitative findings, to help the team develop new TSLC-specific survey scales to ask topic-specific questions of certain groups of students, and to understand other study elements as needs arose.

Further Documentation on the Qualitative Methodologies

The qualitative methods narrative provides an in-depth discussion of the methodological approach, methods, and analysis processes used during the PASS project.

References

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.; Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education, Vol.3 (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Elsevier.

- Rendòn, L. L. (1994). Validating culturally diverse students: Toward a new model of learning and student development. Innovative higher education, 19(1), 33-51.

- Rendòn, L. L., and Muñoz, S.(2011). Revisiting validation theory: Theoretical foundations, applications, and Extensions. Enrollment Management Journal, 5(2), 12-31.

- Hurtado, S., Alvarez, C., Guillermo-Wann, C., Cuellar, M., & Arellano, L. (2007). A model for diverse learning environments. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 27, 41-122.

- Museus S.D. (2014) The Culturally Engaging Campus Environments (CECE) Model: A New Theory of Success Among Racially Diverse College Student Populations. In: Paulsen M. (eds) Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, vol 29. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8005-6_5.

- Rosenberg, M., & McCullough, B. C. (1981). Mattering: Inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Research in community & mental health.

- Strayhorn, T. L. (2019). Sense of belonging and student success at Historically Black Colleges and Universities: A key to strategic enrollment management and institutional transformation. Examining Student Retention and Engagement Strategies at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, 32-52.

- Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676. doi:10.3102/00028312029003663

- Anderson, S. L., & Betz, N. E. (2001). Sources of social self-efficacy expectations: Their measurement and relation to career development. Journal of vocational behavior, 58 (1), 98-117.

- Betz, N. E., & Hackett, G. (2006). Career self-efficacy theory: Back to the future. Journal of career assessment, 14(1), 3-11.

- Cole, D., Kitchen, J. A., & Kezar, A. (2018). Examining a comprehensive college transition program: An account of iterative mixed-methods longitudinal survey design. Research in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9515-1

- Andrich, D. (1978). Relationships between the Thurstone and Rasch approaches to item scaling. Applied Psychological Measurement, 2(3), 451-462.

- Wright, B. D., & Masters, G. N. (1982). Rating scale analysis: Rasch measurement. Chicago, IL: MESA Press.

- Granger, C. (2008). Rasch analysis is important to understand and use for measurement. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 21(3), 1122–1123.